ESA/Hubble & NASA, D. Jones, A. Riess et al.

The Best Planets are Rogue Planets

We can debate the status of objects in the solar system all day long, arguing if little Pluto is a planet or not. But to tell you the truth, any planet in any solar system got the short end of the stick. The real winners of the galactic game are the travelers, the roamers, the rogue planets.

There are a lot of star-bound planets in the galaxy. Estimates are all over the place, but a handy rule of thumb is that there is approximately one planet per star, on average. So for the Milky Way, we have a few hundred billion stars, giving us a few hundred billion planets orbiting those stars.

And for every bound planet, there are between one and ten rogue ones.

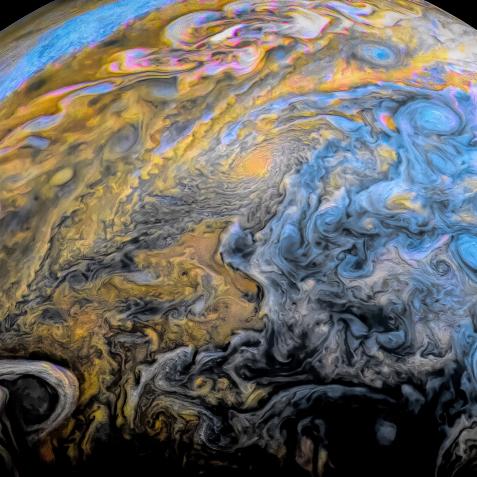

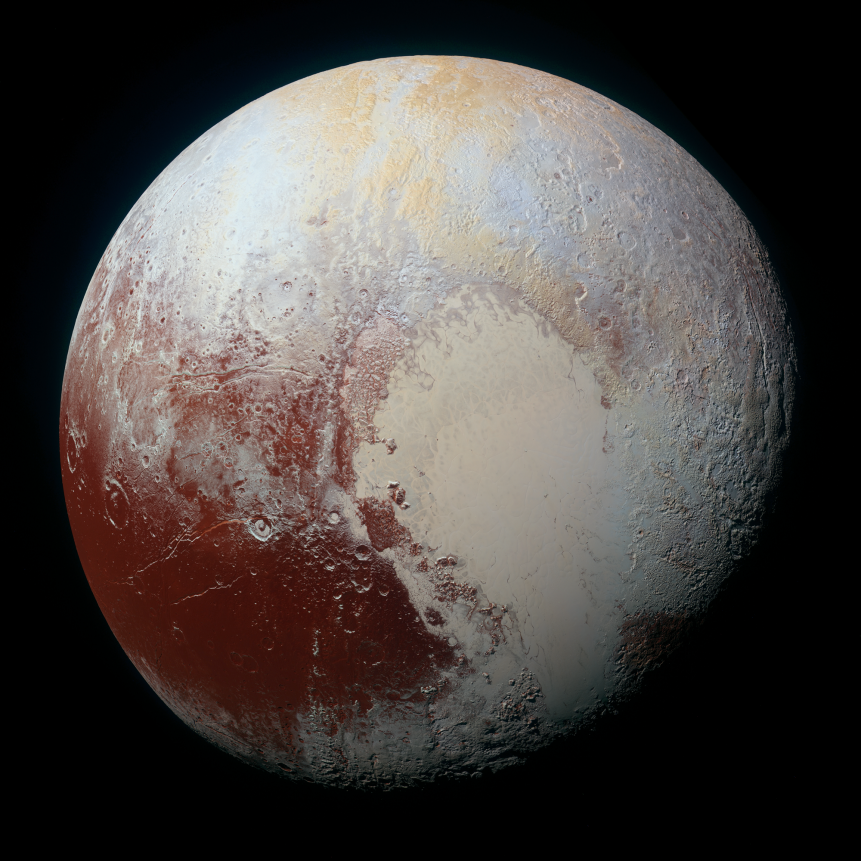

NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Rogue planets can be smaller than Pluto (or bigger than Jupiter).

That’s right: there could easily be a trillion rogue planets wandering the interstellar depths of the Milky Way.

These planets are ferociously hard to detect. For one, they’re small. If they were any bigger, they would-be stars. But they’re not, so they don’t shine brightly, only glowing weakly in the infrared from any internal heat they may have. “Small” and “dim” are a tough combo to overcome in astronomy, so all the known rogue planets – of which there are only a couple dozen – are almost entirely candidates and subject to debate.

Take OTS 44, a potential rogue planet 554 light-years away from us. It’s about 11 times the mass of Jupiter, which is pretty big for planets…maybe too big. It instead may be a different kind of object, known as a brown dwarf. Or take OGLE-2019-BLG-0551 (unfortunately rogue planets tend to get these designations rather than proper names), which might be a rogue planet the size of the Earth. Or just a regular planet on an extremely wide orbit from its parent star.

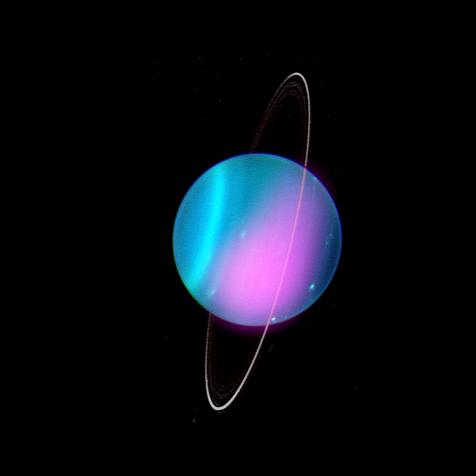

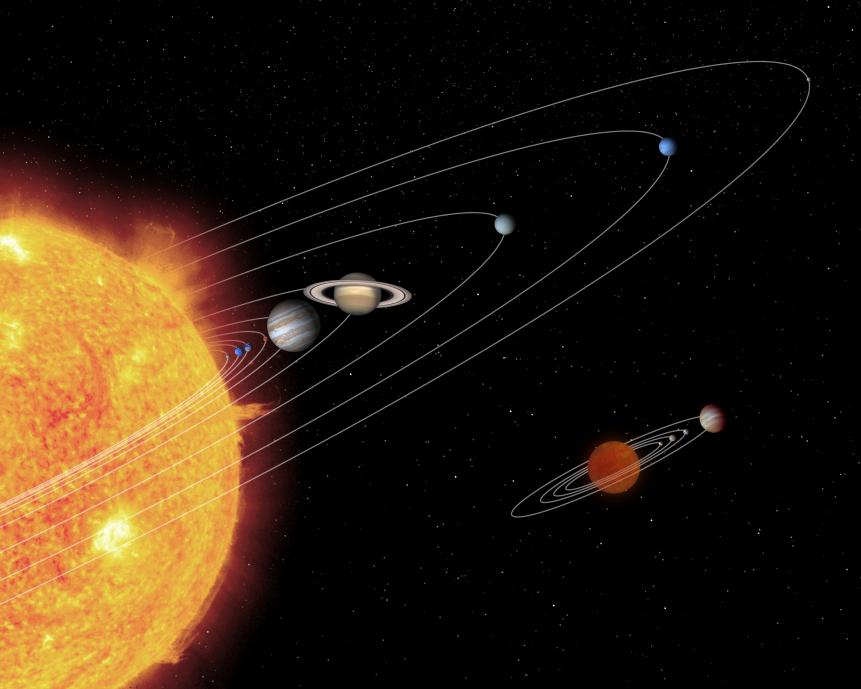

NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle (SSC)

This artist's conception shows the relative size of a hypothetical brown dwarf-planetary system compared to our own solar system. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope set its infrared eyes on an extraordinarily low-mass brown dwarf called OTS 44 and found a swirling disk of planet-building dust. At only 15 times the mass of Jupiter, OTS 44 is the smallest known brown dwarf to host a planet-forming, or protoplanetary, disk.

Despite the paucity of observations, astronomers are pretty dang sure that rogue planets exist. That’s because, in simulations of solar system formation, a lot of planets get formed than wind up orbiting the star. They get kicked out of the home at an early age to live a life on the (interstellar) streets.

What’s really wild about rogue planets is that they might be homes for life. These planets are thought to span the entire range of bound planets, from objects the size of Pluto to beasts bigger than Jupiter. While these rogues will have no star to warm their surfaces, they still have internal heat. If you cut off the Earth from the solar system, the surface would get pretty chilly, but volcanoes and hot springs would still keep running. And where there’s heat there’s the potential for liquid water, and where there’s liquid water there’s the potential for life.

Dive Deeper into the Universe

Journey Through the Cosmos in an All-New Season of How the Universe Works

The new season premieres on Science Channel and streams on discovery+.